Posted on April 28, 2013 by Maria

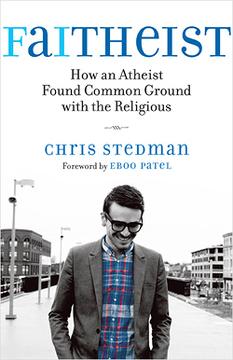

Chris Stedman's book "Faitheist" is subtitled "How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious". For the purpose of this post, let's define religion as the belief in God or the supernatural; in other words, theism. (There is a lot of disagreement about defining religion in this way, particularly amongst "religious humanists", but since this is the way Stedman defines it in his book, let's stick with that.) The book is a personal narrative, a memoir by a twenty-something (strange as that may sound), about starting without religion, finding religion and then losing religion. Along the way Stedman finds a "calling" of sorts to encourage more service work among the non-religious and to bring atheists into the interfaith movement.

Unlike many who lose their religion, Stedman didn't replace belief with sneering disdain. While he went from religious to atheist, he never went the extra step to antireligious. Why?

"For the most part, the antireligious claims I encountered weren't considered critiques of theology, which I've often relished in both academic and interpersonal contexts; they were based in a willful ignorance of what it actually means to be religious and of the way religious lives are lived, and turned religious people into a cheaply mocked caricature."

He never became antireligious because he had relationships with people who were religious, including Eboo Patel, Stedman's boss when he worked at the Interfaith Youth Corps that Patel founded. Stedman never became antireligious because he knew people whose characters and actions didn't fit the caricature.

To most of his atheist colleagues, the idea of interfaith participation made no sense. "When the majority of prominent atheist-identified thought leaders name "the end of faith" as one of the movements top priorities, the idea of participating in organized interfaith efforts can seem contradictory." Not only was it contradictory, it was anathema and resulted in a great deal of vitriol directed at Stedman for even suggesting such a thing.

The idea doesn't seem contradictory to most Humanist Unitarian Universalists. To most of us, that "Common Ground" that Stedman talks about is literal: it is a white-steepled building, often called First Parish, with a weather vane on top instead of a cross or it is a modern meeting hall with stained glass windows depicting flowers, planets or a sunrise. Unitarian Universalists know from interfaith. Because we consider faith to be a personal matter, there is no dogma or creed that unites us, only adherence to seven principles that almost directly parallel the latest Humanist Manifesto. It's almost a cliché in UU circles to paraphrase John Wesley, “We need not think alike to love alike.” Another UU chestnut is the "You're a Theist, I'm a Humanist" song. It pokes fun at the fact that the Humanism-theism debate has been going on in congregations for a very long time but that we still end up friends in the end.

Everyone agrees that humans are social creatures and that (most of us) thrive in community. We are also more effective at taking action when we do it together. Being part of a Unitarian Universalist congregation is not for everyone, particularly not for those atheists who consider it "accommodationist" to work and socialize with people with whom they disagree regarding metaphysics. But how many of us are completely fixed in our thoughts about religion? Most anti-atheists accuse us of being arrogant, negative and selfish. This is certainly a caricature and a stereotype. As the LGBT movement taught us (something that Stedman also shows a great deal of experience with in his book), the best way dispel a stereotype is to have a relationship with the "other". By being openly atheist in UU communities where the overriding demands are service, compassion and thoughtfulness, we are showing people that their stereotypes are wrong. By standing up for reason within those communities, we are showing open-minded people that there is an alternative to supernaturalism that also leads to fulfillment and, for many people, that is their path to Humanism.

I guess it is not surprising that I see much of Unitarian Universalism in "Faitheist", after all Stedman got a master's degree from Meadville Lombard Theological School which is primarily a seminary for UU ministers, and the book was published by Beacon Press, the publishing arm of the Unitarian Universalist Association. In fact, I was surprised to see so little of UUism in the book. Why is that? Is Humanism within UUism such a lost cause that Stedman would prefer not to be associated with it? There are approximately 160,000 UUs in America, roughly half of whom identify as Humanists. That's a big opportunity for organized Humanism! A CBS documentary "Religion & Spirituality in a Changing Society", recently profiled the UUA and the Harvard Humanists in Cambridge, MA where Stedman now works as two successful communities that are attractive to the "Nones", those without any affiliation with organized religion. That's a big opportunity for UUism!

Like Chris Stedman, I guess I'm a faitheist; I don't accept caricatures. I think engagement is better than estrangement. I won't politely ignore our differences if you are motivated by your belief in God -- I will ask you about your beliefs and share mine. Then we'll get down to work together.

1 Comments

I especially liked your reference to "You're a Theist, I'm a Humanist". I got linked to Humanism by reading "Good Without God". Thanks for your thoughts about Chris Stedman. I'm going to buy "Faithest". I used to like the UU church, but am not excited about my local UU church. Maybe that is what happened to Chris.

Dave Moore

Add your comment